Program

George Frederick Handel

Trio Sonata in F. Major, Op. 2, No. 4

Francis Poulenc

Trio

Mikhail Glinka

Trio Pathétique in D Minor

Dimitri Shostakovich

Romance from “The Gadfly” (film)

A Spin Around Moscow

Poulenc Trio

The Poulenc Trio is an unusual instrumental combination of oboe, bassoon, and piano. Since its founding, the Trio has greatly expanded the repertoire available for this instrumentation with more than 20 new works written or arranged for the group.

Program Notes

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)

Trio Sonata in F Major, Op. 2 No. 4 (1733).

Performance time: 11’

In 1685, mirabile dictu, George Frideric Handel, Johann Sebastian Bach and Domenico Scarlatti were all born this year. Titans of the Baroque era and beyond, Scarlatti and Handel met in Italy and greatly appreciated each other’s music. Bach never met Scarlatti or Handel, though he was quite familiar with their works.

George Frideric Handel (1685–1759). No wig.

Handel wrote operas, oratorios (most famously, Messiah), songs, concerti, keyboard works, and thirteen trio sonatas, an extremely popular form at the time. Despite its name, a Trio Sonata is written for four instruments, with two high pitched instruments playing equally important melodic lines, a third lower instrument playing a bass line, and finally the fourth “basso continuo” instrument playing harmonic support. Note that the lower instrument’s part and the continuo can be combined and performed by just one instrument, such as a harpsichord or piano. This “basso continuo” instrument plays from a “figured bass,” in which the desired harmonies are notated as numbers (“figures”) rather than as written-out chords, much as today’s jazz or folk songs are notated. Trio sonatas used the typical instruments of the day, such as the violin, viola, cello, flute, oboe, bassoon, recorder, harpsichord, and theorbo. Illustrating this genre’s instrumentation flexibility, in today’s performance the upper parts are played by the oboe and bassoon, with the piano playing the bass line and the harmony together. Musicians playing these sonatas are expected to show off a bit and to provide their own period-appropriate trills, runs, turns, etc., just as today’s jazz musicians add their own “licks,” so be sure to listen for these ornaments.

The ingeniously intertwining lines of Trio Sonatas, the fact that they prized fluent conversational interchange over inconvenient virtuosity, and their flexible instrumentation contributed to their popularity with professional and amateur musicians alike during the Baroque period (1600-1750). They were written and published well into the mid-18th century, but the emerging Classical style ousted them with its (entirely separate) development of string quartets and instrumental sonatas with keyboard accompaniment.

To illustrate figured bass technique, here are the opening measures of today’s trio sonata with its figured bass notation (single note in bass clef with little numbers below—6, 7, 4/2). Skilled baroque keyboard players who are well versed in harmonic structure can read or “realize” these numbers very easily and turn them into chords or harmony.

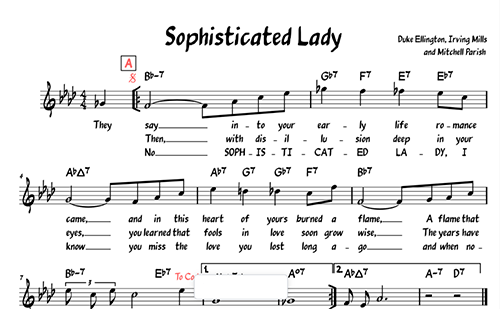

And here is an example of a jazz chart with harmony given as chord names (Bb-7, Gb7, etc.) over the melody. Skilled jazz players translate those chord names and numbers into chords just as baroque figured bass performers do.

To illustrate this genre’s instrumental flexibility, here are three performances of our sonata today, performed by different forces in terms of both number of and kinds of instruments. A note on performance practice: if you listen to the opening measures of each example in rapid succession, you’ll notice that the tunings are different from one another. Musical pitch varied widely from place to place during the Baroque era. It was generally lower than it is today, but there were exceptions and sometimes it could be even higher. Modern measurements of baroque instruments show that the pitch would mostly have varied between A=380 and A=480 Hz (Hz = Hertz, a measurement of cycles per second). In fact, it was only in 1936 that the American Standards Association recommended that the A above middle C be tuned to 440 Hz. Today, many baroque ensembles who use harpsichords and other period instruments often tune at A=415 Hz or lower, since harpsichord strings sometimes break at the higher tension required for A=440 Hz. This sounds at least a half tone lower than A=440 Hz. Offsetting the harpsichord issue is the fact that modern wind and keyboard (i.e., piano and organ) instruments are tuned to A=440 Hz, a major consideration in choosing tuning. Lucky strings can easily adjust either way.

All this raises the question: what is “perfect pitch”? Perfect to which Hz tuning, if A can be authentically tuned to anywhere between 380 and 480 Hz? I leave it to you—comments?

L’Ecole d’Orphee’s version with four instruments: violin, recorder, cello and harpsichord (maybe A=415 Hz or lower, maybe because of the tuning needs of that harpsichord).

Ensemble Augelletti’s reading with five instruments: recorder, violin, cello, theorbo, chamber organ (A=440 Hz, perhaps because of the fixed modern tuning of the chamber organ).

The Muses’ Delight’s realization with three instruments: baroque transverse flute, baroque violin and baroque cello (note: no keyboard, and with baroque period instruments, and tuning which lies somewhere between the previous two examples).

Francis Poulenc (1899–1963)

Trio for Oboe, Bassoon and Piano FP 43 (1926).

Performance time: 14’

In 1926, Alexander Calder created “Cirque Calder” sculpture; Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises published; Queen Elizabeth, Marilyn Monroe, Miles Davis and Fidel Castro are born.

Francis Poulenc (1899–1963).

French music critic Claude Rostand quipped, “In Poulenc there is something of the monk and something of the rascal." Poulenc, the composer of the deeply religious and serious opera “Dialogues of the Carmelites,” was also openly gay and led a scandalously wild life in his earlier years. He was the most prominent member of a famous group of French composers known as Les Six (the others were Auric, Durey, Honegger, Milhaud and Tailleferre of whom only the last three plus Poulenc remain familiar). Their music was in part a reaction against the influence of what they saw as the excesses of German music represented by Wagner and the high seriousness of 1920s modernism (like the serial music of Schoenberg and his pupils). They aimed to write in a more straightforward and direct way than Debussy and Ravel, and the trio we hear today is a splendid example of the light-hearted style with which Poulenc and Les Six are associated.

Poulenc wrote this trio, his first major chamber work, while staying in Cannes on the French Riviera, and he dedicated it to the great Spanish composer Manuel de Falla “to prove to him for better or for worse my tender admiration.” The first movement of this piece starts with a brief, slow introduction notated “librement” or “freely.” It then moves into a Presto section which is effervescent, witty and charming, with alternating episodes of the two themes. The brief second movement is an extended lyrical and lovely song, with the two double-reed instruments sometimes exchanging their parts of the melody, sometimes playing together. And finally, the high-speed Rondo is full of humor and sparkle, with varied interludes between repetitions of the principal theme moving along with good spirit until the sudden, abrupt surprise ending.

Click here for an exciting 1957 performance with baroque oboist Pierre Pierlot, bassoonist Maurice Allard (regarded as the greatest French bassoonist of the 20th century), and Francis Poulenc himself at piano.

Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857) Trio Path étique in D Minor for Clarinet, Bassoon and Piano (1832).

Performance time: 15’

In 1832, Andrew Jackson elected to second term as President; Charles Darwin, on board HMS Beagle, starts his scientific explorations; Louisa May Alcott is born.

Mikhail Glinka (1804–1857).

Considered by many to be the father of modern Russian music, Glinka was an unlikely hero. An aristocrat, a dilettante and an incorrigible hypochondriac, he became a determined reformer of Russian music and inspiration for later Russian composers. As a boy living on his father’s estate, Glinka developed a love for the local folk music which remained with him for life. In 1828, Glinka set off for Italy, where he met Donizetti and Bellini and was subsequently drawn to Italian opera. Glinka mastered the Italian operatic idiom, but by 1833, he found himself dissatisfied with composing in a style that felt alien. He endeavored from this point forward to compose “in a Russian manner” and thereby find his voice. With a fundamental grasp of the lingua franca of Western European composers, Glinka, largely self-taught, cultivated a musical language that integrated a Russian character with classical and operatic styles.

Glinka wrote this while studying opera in Milan. While there, Glinka had several unsuccessful love affairs. His caption above the score is operatic in itself, and reads, “I have only known love through the misery it causes. Perhaps this unhappiness is most fully expressed in the slow third movement of the Trio. However, much of this trio is an exuberant work. The ensemble’s palette of timbres has much to do with its character, with clarinet and bassoon evoking bell-like laughter in their upper registers. In the first movement, the winds serenade one another while the piano imitates and ripples underneath. The second movement is typically playful yet balanced. The emotional center of the work is the Largo, the longest of the movements, in which the clarinet sings, the bassoon answers, and then the two play lyrically together. The finale begins with the first movement’s theme, then continues with arpeggios and ends with stormy emotion.

Click here for an excellent performance by undergraduate students at Curtis Institute of Music. Yan Liu, clarinet, is currently studying at the Juilliard School, having studied at Curtis with Anthony McGill, principal clarinet of the New York Philharmonic (McGill has strong Chicago connections as a board member of Chicago-based Cedille Records and graduate of Chicago’s Merit School of Music). Doron Laznow, bassoon, was appointed last year to Second Bassoon of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra. Bolai Cao, piano, was awarded the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts at the Eastman School of Music in Spring, 2023.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

Romance from film “The Gadfly” Op. 97 (1955);

A Spin Around Moscow from operetta “Moscow, Cheryomushki” Op. 105 (1958).

Performance time: 6’

1955 Argentinian dictator Juan Perón ousted; Lolita published. 1958 Eisenhower created NASA.

A rarely laughing Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975) in London, 1960.

All his life Shostakovich had a fondness for light music, movie soundtracks, operetta and musicals. Today we will have two very brief examples.

Shostakovich wrote one of his most popular and accessible film-scores for “The Gadfly,” a highly successful film in the Soviet Union. A sugary costume drama described as a cross between The Three Musketeers and The Scarlet Pimpernel, the Romance was one of its most popular tunes.

The second work is from an operetta characterized as an entertaining satirical romp, mocking the corruption and idealism of the USSR in the post-Stalin era. It pokes particular fun at Khrushchev’s notoriously overambitious plan to rehouse almost the entire population in hastily built and splendidly up-to-date apartment blocks, complete with such wonders as fridges, elevators, etc.

Click here for a romantic take on the Romance.

Click here for an orchestral version of A Spin Around Moscow.

—Program Notes by Louise K. Smith

louise_smith@mac.com

With thanks to Patrick Castillo

Poulenc Trio

Subscribe

Today!

Individual tickets may be purchased at the door (cash or check only) immediately before each concert.

All concerts are held at a private club just off Michigan Avenue in Chicago.

Call or email for more information

815-314-0681

office@ChicagoChamberMusicSociety.org